How do Hyrum’s Law and Postel’s Law affect API designs?

Luckily for us humans, and especially that narrow subclass of humans who build APIs, API design is a field that has not been automated or botified… yet. Sure, one can point at a database schema and generate what one can label an “Application Programming Interface.” But it is an API only in a literal sense — and certainly not in a RESTful one. It does not provide any of the benefits of designing an API abstraction layer, such as decoupling your API from the back end. (See Nordic APIs’ How To Build And Enforce Great API Governance.)

One of the reasons API design is more an art than a science is that human intelligence is still required to weigh the competing forces that arise. There are numerous API design cookbooks available, such as REST API cookbook, The Design of Web APIs, RESTful Web APIs, and Design and Build Great Web APIs. These resources offer several categories and layers of design guidelines that are easy for humans to understand and apply… less so for an artificial intelligence. The art of API design lies in weighing and making decisions around those tradeoffs.

Consider two human-centric software design principles which are so impactful they are better characterized as laws:

[John] Postel’s Law

TCP implementations should follow a general principle of robustness: be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others.

Postel’s Law is so darn useful that it has been generalized away from the narrow realm of TCP implementations as the Robustness Principle:

Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept.

Postel’s Law focuses on making service implementations more robust by allowing for interfaces and messages to evolve over time. A nice consequence of Postel’s Law is that it can make APIs easier to use, which we’ll see in a moment.

Hyrum’s Law

With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

While Postel’s Law is one of those guardrails that help you design robust APIs, Hyrum’s Law, coined by Hyrum Wright, is one of those 1,000-foot cliff drop-offs along that narrow, winding, gravel mountain road. You know, the one without the guardrail. Hyrum’s Law is so treacherous; it even has an XKCD manifestation.

The problem that our human brains can solve but the robot overlords can’t (yet) is how to weigh Postel against Hyrum. You probably want something a little more concrete (unless you’ve already driven over that cliff, in which case you want something a little more silk-like).

Let’s look at some examples.

Examples of Postel’s Law in Action

Example 1: Imagine you have been tasked to build an API for authors to submit content for publication on Nordic APIs’ site. One API operation in your “Submissions API” accepts the author’s contact phone number. With Postel’s Law in mind, you design the API to accept multiple formats, such as "(910) 555-1234" or "910.555.1234" or "9105551234". You also design the API to always return E.164 formatted phone numbers such as "+19105551234". This interpretation of “Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept” yields an API that is easier for clients to use:

- Clients can pass phone numbers in multiple formats according to user input preferences; each client does not have to normalize phone numbers.

- API consumers do not have to worry about parsing/supporting various phone number formats returned in the API’s responses, only one well-defined format.

Example 2: The Submissions API operation to search submissions has a query parameter, defined by the OpenAPI Specification (OAS) notation:

The OAS relies on JSON Schema (see 7 API Standards Bodies To Get Involved With) to define the types of properties, parameters, and request bodies. So, clearly, one can pass ...?published=true or ...?published=false. However, some client languages don’t use true and false tokens for Boolean values. Python, for example, uses True and False instead.

Should one apply Postel’s Law and be liberal in what the API accepts here, as with the phone numbers? It may be tempting to code the API to accept ?published=True, ?published=TRUE, ?published=t, or even ?published=1. All are possible representations of a “true” value in various client programming languages. Your implementation framework may even have a nice utility that can convert all kinds of values into Boolean values. However, this example and the next show the risks of adding too much flexibility in input validation.

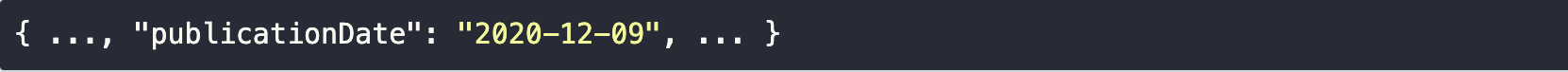

Example 3: Your API has an operation that accepts a request body schema with a property, publicationDate. Thus, a valid JSON request would specify the date as follows:

Let’s say you are on a Postel’s Law roll and code the implementation to accept other date formats, such as "2020/12/09" or "Dec 09, 2020" for the date December 09, 2020, to make the API easier to use (ignoring the fact that "12/09/2020" is ambiguous). Knowing it is critical to validate all user input in a pubic API, you find a nice open-source library that parses dates. But a year later, the team migrates the API implementation to a new language runtime and a new library that also accepts these formats. Such backend changes should not affect API consumers. Unbeknownst to you, some clients have been passing dates in "09-Dec-2020" format. The new framework and library don’t handle this, nor does it support all the “truthy” values you previously allowed for the ?published= query parameter. Hyrum’s Law has struck!

One can use more elaborate OAS/JSON Schema constructs to be more liberal in what the API allows, such as JSON Schema oneOf or anyOf, or using pattern: instead of format: .... However, such alternatives obfuscate APIs, and that’s the enemy of clarity and ease of use. Also, not all client languages and SDKs support oneOf/anyOf schemas.

API Evolution

The original intent of Postel’s Law was to account for evolution of the interface. (See also Nordic APIs’ What’s The Difference Between Versioning and Revisioning APIs?.) Examples of evolution in the API space include adding new properties to a JSON schema. This is a core principle of “good” REST APIs: the service and clients should be free to evolve (in a compatible manner) independently of each other. For example, the first release of the publishing API may allow passing only the title and publication date properties:

A new release of the service may add a new revision property, so requests may look like:

A robust service would allow this request (even in the first release!) by ignoring (and perhaps logging) properties that it does not recognize, rather than treating them as an error. Clients who consume such content should also be lenient in what they receive. A client built for the first release of an API should not fail if it connects to the newer release of the API that includes new properties.

One consequence of API design that Postel’s Law tells us: when defining JSON Schemas for our APIs, avoid using additionalProperties: false

Doing so slams the door in John Postel’s face!

Hyrum’s Law states that all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody. This includes behaviors that are not explicitly accounted for in the API design or documentation, such as the "09-Dec-2020" date format above. If one considers an API definition to be a software contract, then Hyrum’s Law means consumers have found (and depend on) loopholes in that contract. Industry veterans are all familiar with a customer who has come to rely on buggy behavior, which they quickly learn about only after releasing a bug patch!

Hyrum’s Law and API Evolution

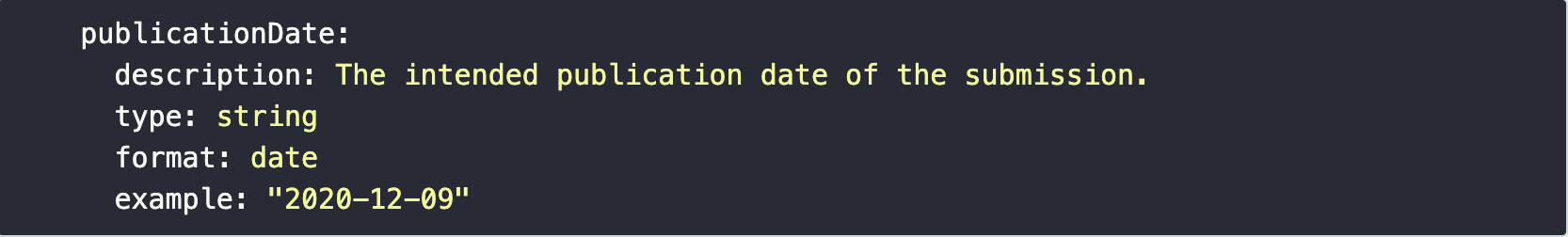

APIs must evolve over time. Hyrum’s Law tells us that such change will be painful. Imagine you did not provide an OpenAPI definition with your first Submission API releases, but you chose to add it after several requests from consumers. You describe the publicationDate string property and its need to represent a date value:

Hyrum’s Law also means pain here. An API design that adheres strictly to the OpenAPI Specification and JSON Schema validation does not always allow for the “be liberal in what you accept” clause of Postel’s Law.

JSON Schema tells us that a string with the date format must follow the RFC 3339 "MMMM-DD-YY" format. API frameworks and libraries based on OAS and JSON Schema may not allow input that does not pass strict JSON Schema validation.

In effect, this design choice imposes a stricter constraint on the API. Other formats that users have come to depend on are not allowed. To maintain compatibility, you are forced to abandon the use of format: date for the property to maintain your kinship with Postel’s Law. (With luck, you find out before you publish the OAS API definition.) But to guard against Hyrum’s Law, you need to specify all the allowed date formats.

Another example of Hyrum’s Law wreaking havoc would be a client that passes:

to the above publishing example. Perhaps because they are reusing a response from another API that includes revision, and they simply don’t remove it before calling your Submissions API. This behavior was allowed in the first release, and perhaps the client even comes to depend on this behavior. However, once the service adds a revision property with type string, that client request will cause an error in the Sumissions API. Something as simple as adding a new property can break existing consumers!

Unfortunately, there are many such ways that API evolution can have such ill effects: adding a value to an enum list or changing the maxLength of a string from 80 to 100 may break a consumer. Even changing the HTTP response code for an erroneous call from 400 to 422 will change an “observable behavior.”

I highly recommend Gareth Jones talk, Your API Spec Isn’t Worth the Paper It’s Written On, presented at Nordic API Austin Summit 2019. Gareth points out many ways that even small changes in APIs or their implementations can break clients.

Balancing Postel and Hyrum in Practice

The main impacts of Postel’s and Hyrum’s laws arise: To prevent unintentional dependencies on unspecified data and behavior, the API definition would need to do the following:

- Enumerate all the variations on how developers will use it, such as listing all allowed formats of all input and all possible API call sequences. The goal is to turn the API software contract into an “iron-clad contract” and remove all loopholes.

- Disallow any input that deviates from the new, strict API definition — even “harmless” ones. This must start with the first release by explicitly failing operations and data outside the API contract. Thus, no client can come to depend on those behaviors.

Clearly, with any non-trivial API, it is impossible to do either! Even listing only common variations can add significant bloat to the API definition. Unfortunately, larger, more verbose API definitions are harder to use compared to concise API definitions. They also add significant cost to the implementation, including developing exhaustive, comprehensive regression tests. Avoiding the cliff of Hyrum’s law is at odds with Postel’s Law of being liberal in what you accept. Trying to follow both means giving up easy to understand, concise APIs, or it locks you into a backend that cannot evolve.

The ultimate artful engineering solution is to be aware of both laws and weigh them in each API design decision. One tactic is to set reasonable expectations with your consumers about API evolution and change. Don’t be an automaton when it comes to API design. Instead, use your experience and intelligence to design APIs that respect the boundaries laid down by Hyrum and Postel and which can evolve as your API consumers’ needs change.

About David Biesack

As VP of API Products and Lead API Architect at Apiture, David is responsible for REST API architecture, design, governance, developer experience, and tools. David is interested in whatever makes software [development|developers] better, stronger, faster.